Trykkeriet is very pleased to open P U L S E by Gunilla Klingberg on November 30th from 7 p.m. The solo exhibition consists of a series of 5 large silkscreen prints that were produced in collaboration between the staff at Trykkeriet and Klingberg.

I image it as an impulse…

I imagine it as an impulse: confronted with a closet full of clothes left by a loved one, the will to see them with different eyes. Eyes that don’t register the cut, the colour, the label, don’t take in the dead person’s taste and preferences, not even their style, but with eyes that want to see the inside.*

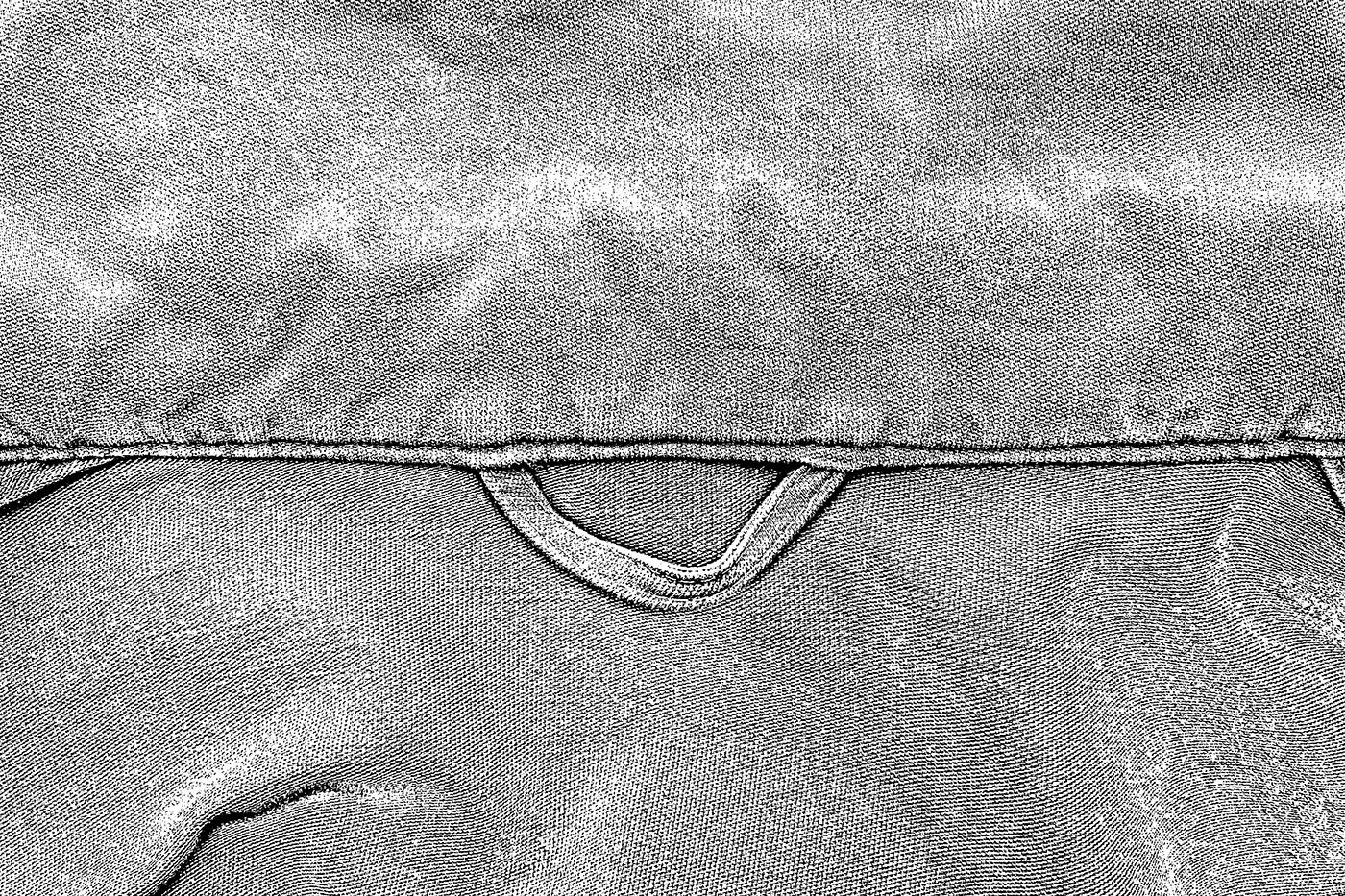

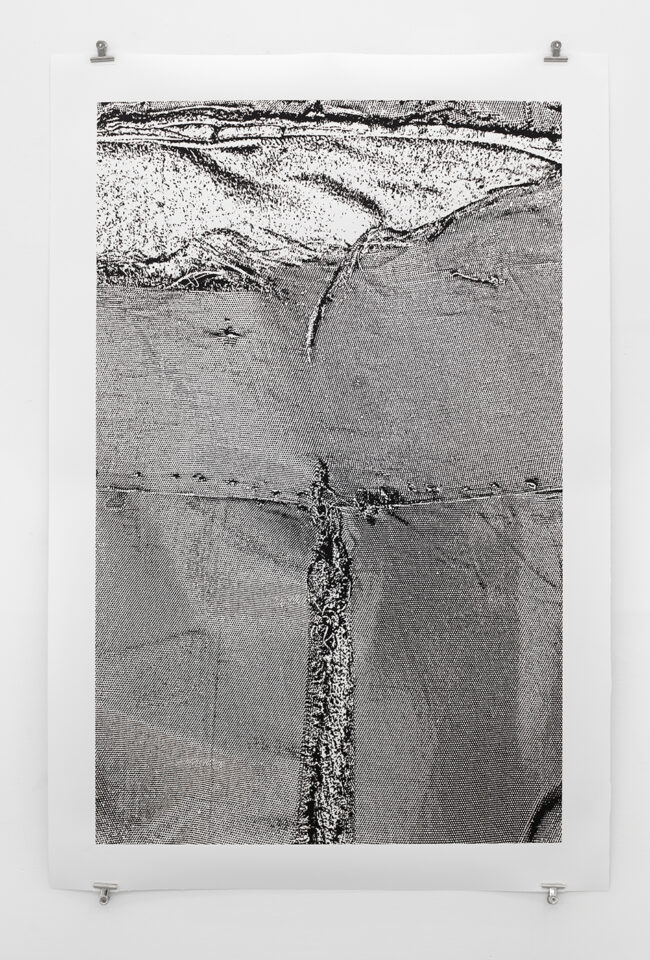

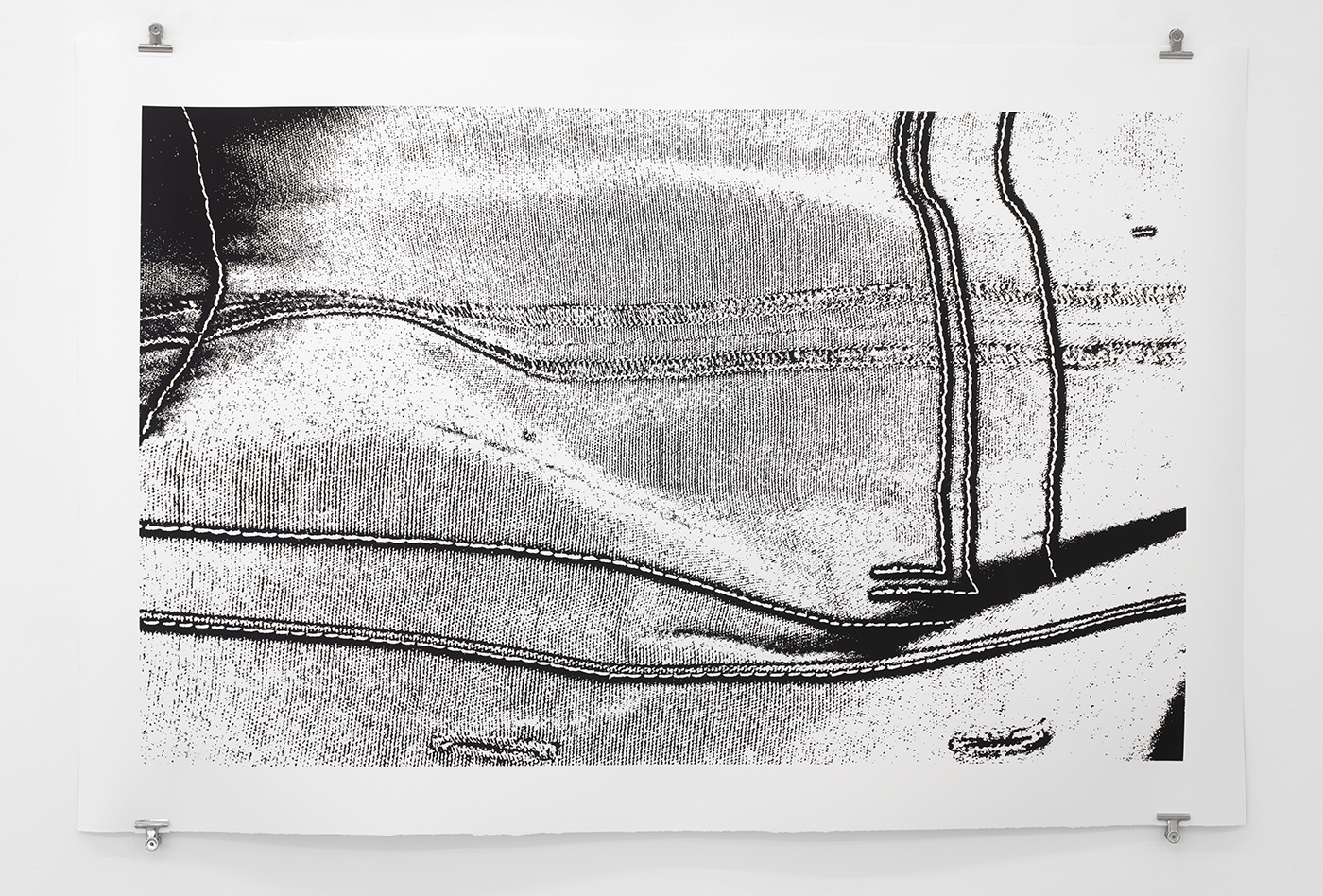

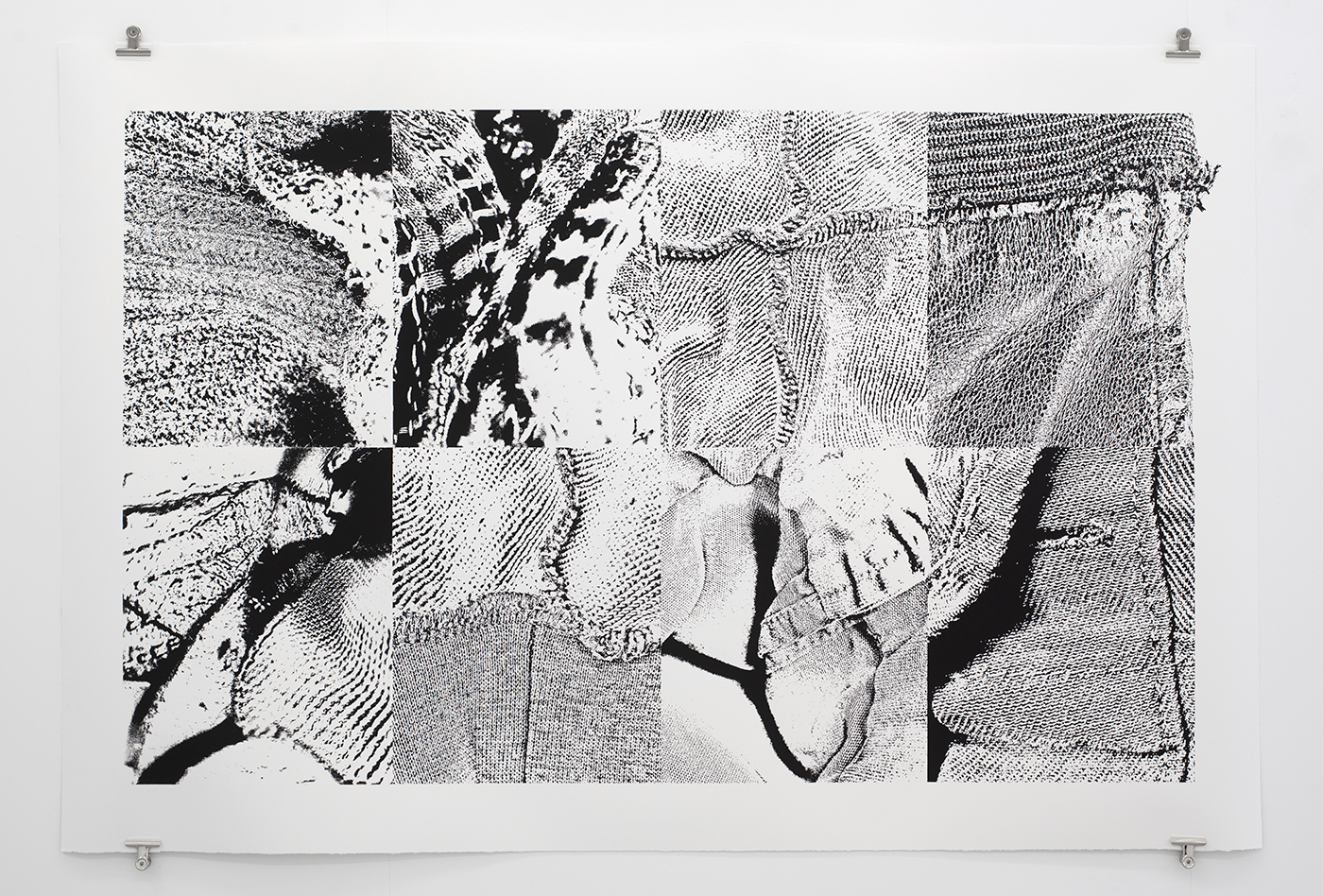

More precisely, those parts of the clothing that have been in contact with the body at points where the pulse is most tangible: the top of the foot, the back of the knee, the wrist, the side and back of the neck, the temple; the interior of a shoe, the cuff of a sweatshirt and of a jacket, a shirt cuff, jacket collars, the crotch from a pair of jeans, a shawl, a hat.

Places where the heartbeat comes to the surface quickly like tiny but palpable elevations, gentle pressure against the fingertips. Or against the fabric. Heartbeats. No, not in plural, nor isolated from one another. The pulse. The unity of beats and the pauses between them, a pulse. A still movement – perhaps that is why its intensity is increased both by the pulse becoming faster and slower, while the intensity of other movements is typically said to escalate only with the increase in speed.

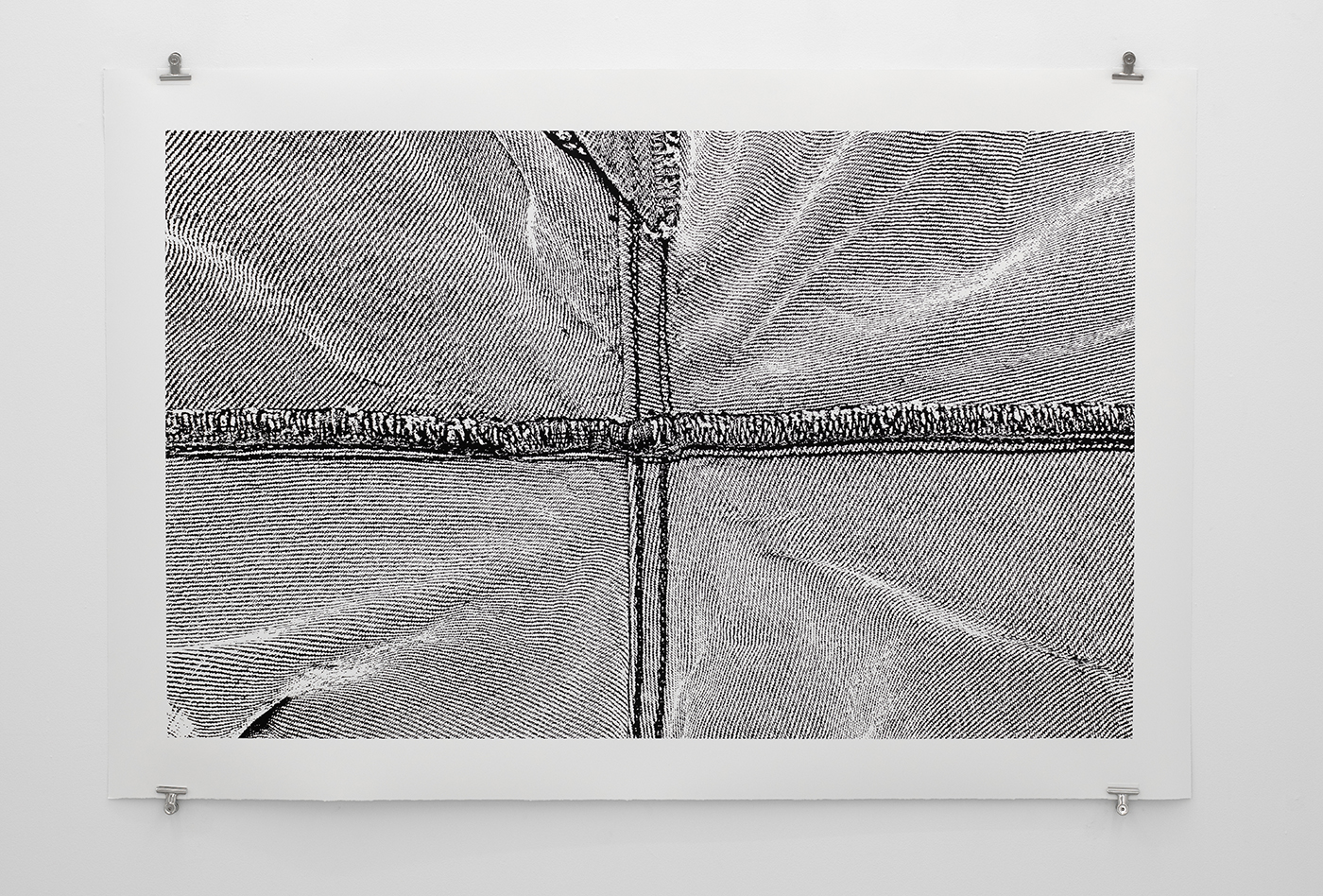

It is fitting, somehow, that Gunilla Klingberg didn’t photograph the clothes, but scanned them. The scanner, I imagine, sees differently, with more tactility.

Standing in front of the artworks in Gunilla’s studio, she also showed me some Duchamp quotes about something he called the ‘infrathin’. “The infrathin is when the tobacco smoke also smells of the mouth, which exhales it.” Duchamp further exemplified this by citing the sensation of warmth on a seat from a body that has just left it, and the sound made by velvet trouser legs rubbing against each other when walking. He has no visual examples. I imagine that Klingberg has attempted to scan the remains of heartbeats. Or rather the pulse. The presence and absence of heartbeats, which the pulse combines like the smell of tobacco and breath. The pulse sensed at the fingertip together with the fabric. Isn’t scanning perhaps more like running your fingers across something, rather than simply looking at it. Maybe sight can be tactile too, somehow? Things may feel rugged through sight, and warm, cold, damp or dry. And maybe a pulse echos through fabric.

My eyes were searching for it – that pulse, any sign of it. That strange still movement, in which presence and absence interchange, whilst always remaining present. In itself it gives the suggestion of moments coming and going, yet at the same time a motion so present that it’s never lost, but forever here.

Klingberg mentioned the books Vibrant Matter and Vibrant Death by Jane Bennett and Nina Lykke respectively, in which both authors shift their focus from the human experience of things to theorising a ‘vital materiality’ that runs through and across bodies, both human and nonhuman. Gunilla also mentions the trembling mescaline drawings by Henri Michaux, which he began making after his wife had died in a fire. What he sought in drugs were not artificial paradises (he declared even real paradises to be boring), but a “redistribution of sensibility”, which allowed him to understand the drug visions differently. The mountains that people observe during their mescaline trips are not visible and never have been. What is actually being seen are ripples and vibrations interpreted as mountains. The vibrations are both sensibility and matter, together. They could also be the ‘objects’ of tactile vision.

After scanning the fabric, Klingberg enlarged the images without using a raster. What the raster does is to break down continuous elements, like waves or colour tones, into discrete units, raster points or atoms, which form the image. Seen from the right distance, an optical impression of unbroken tones is recreated (which doesn’t exist in the points alone). When rejecting this technique, she states that “it is instead the image itself that is the raster”. So the images aren’t actually meant to depict anything, but help us give the impression of continuous elements that, without the raster, could not be conveyed at a distance. You’re not supposed to look at the image, but through it, be supported by it, and to touch something with your gaze. The vibration isn’t visible as shapes in the image, but can be viewed ‘inside’ the image.

The pulse, I feel, should be possible to visually perceive within, be registered (or even ‘seen’, as Michaux emphasised) as a unity, not as an accumulation of heartbeats and pauses. Rather, as a continuity which cannot be atomised, which cannot be understood by its raster points. Something meditative captures the gaze. In a strange way, it feels as if my peripheral vision captured the centre too, making everything seem as if seen from the corner of my eye. The sensation reminds me of a line from J.M.G. Le Clezio’s L’extase matérielle that goes something like: silence returning to silence, borne out of silence. In an infrathin moment that’s how the gaze, and that which is gazed upon, feel.

The raster image unlocked something that momentarily touches me and makes me question whether life and death may have an infrathin relation, like the tobacco smoke and the breath.

One of the images, a collage, looks as if it’s almost about to become a new body, some sort of magical doll. It veers towards three-dimensionality. In one way the image repeats the raster format, whilst from a different perspective it looks as if the pieces of fabric are striving to go beyond their limitations and begin to unite. Cuffs and collars lying next to each other are connected, and you imagine a body made entirely of a beating pulse. A temple without a face, next to a wrist without a hand. I have a vision of a pulse circulation system, which could exist in fabric without the need for blood, like smoke that needs no tobacco or breath that needs no lungs. Only finer vibrations.

Lars-Erik Hjertström Lappalainen

Art critic and writer, including of Big Dig. Om samtidskonst och passivitet [Big Dig. On Contemporary Art and Passivity.]

*This isn’t the first time her works steer themselves towards the inside. The last two pieces she completed with Peter Klingberg Geschwind, whose clothes we are looking at here, pointed in that direction. After Trafic, a tall public sculpture constructed from colourful traffic signs, they spoke about the way the work’s interior had become like its own piece. If you walked underneath it and looked up you would see a large metal-coloured mandala. And when they made Lifesystems – Nonspace, an inflatable sculpture stuck between two trees, they only discovered right before the opening that it was the inside that, completely unintentionally, had become the actual work, which they then presented. In both cases there was something that had come loose on the inside, and appeared in its own right.

Translated from the Swedish by Anna Tebelius

Thank you list:

The artist would like to thank the following for meaningful studio conversations throughout the process, and for sharing their insights about this challenging work: Thomas Elovsson, Martin Gustavsson, Theodor Ringborg, Bettina Pehrsson, Asbjørn Hollerud, Lars-Erik Hjertström Lappalainen, Kristofer Lundström and Fia Backström.

A special thanks to Aron Agélii, who made the connection to Duchamp’s idea of the infrathin.

And as always: Thank you Peter.

The exhibition received financial support from IASPIS – International Artist Studio Program Sweden, the Norwegian Arts Council, the Municipality of Bergen and Mobility Funding from Nordic Culture Point.

Gunilla Klingberg (born 1966) lives and works in Stockholm.

She has had solo exhibitions in museums and galleries throughout Europe and was included in ART ENCOUNTERS BIENNIAL (2019) Timisoara, Romania; 11th Gwangju Biennale, THE EIGHTH CLIMATE (WHAT DOES ART DO?), South Korea (2016); the 10th Istanbul Biennial (2007); Philagrafika Festival: The Graphic Unconscious (2010) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; ReShape! IASPIS at the Venice Biennale (2003).

Solo exhibitions include: Skissernas Museum, Lund (2024); Galerie Nordenhake, Stockholm (2017); Rice Gallery, Houston, USA (2013); Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada (2014); Times Museum, Times Rose Garden, Guangzhou, China (2015); Malmö Konsthall, Malmö, Sweden (2014); Eastside Projects, Birmingham, England, (2013); Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm (2009); KIASMA Museum of Contemporary Art, Studio K, Helsinki, Finland (2004)

Large-scale public commissions include the New Slussen bus terminal (2025) in Stockholm, Burrard Place (2021) in Vancouver; the Triangeln Railway Station (2010) in central Malmö, Sweden, and the Nye Akershus Hospital (2008) Norway.

During the academic year 2023/24 Klingberg was an adjunct professor at the Royal Insitute of Art. In autumn 2025, she will be resident at the ISCP in New York through the Swedish Arts Grants Committee.

Klingberg’s work is part of the permanent collections of Moderna Museet, Malmö Konstmuseum, Koç Foundation, Istanbul, Turkey, FRAC, France among others. She has been a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts since 2019.

The artist in residence was made possible with support from Nordic Culture Point